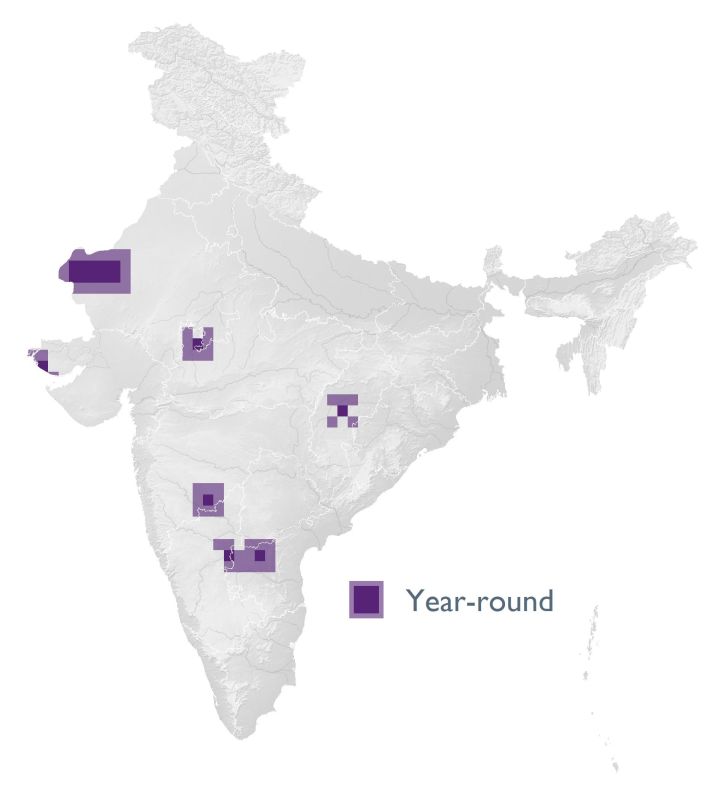

The Great Indian Bustard Ardeotis nigriceps is one of India’s most charismatic (and rarest) birds. It is an endemic species that is distributed across the states of Rajasthan, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. Bustards also occur in Pakistan, although are heavily hunted. They are locally known as Godawan, Hoom, and Gaganbher.

The Great Indian Bustard is strongly tied to scrub habitats, grasslands—arid and semi-arid—as well as a matrix of grassland and agriculture. In fact, many farmers across its range have actively encouraged bustards using their farmlands, and have even made conditions favourable for them to breed in their farms, without disturbance.

The Great Indian Bustard is regarded as one of the heaviest flying birds in the world (with adult males weighing as much as 14kg). They stand as tall as 1.2 metres. The bustards have a long white neck with a black crown. While the male has a more pronounced white neck, the female has a grey neck. The female is also smaller, has a white supercilium (as opposed to the black crown descending to the eyes in males), and lacks the black breast band. They also have more white spotting on the wings than the male.

One of the most interesting aspects of the Great Indian Bustard is its mating system that involves a ritualised event called lekking. This involves male individuals actively defending a choice spot and booming—making a deep, low pitched sound—to attract females in the vicinity. During this process, a male unfurls its extravagant white gular pouch and ‘booms’ in several directions in a fit of display. The Great Indian Bustard lays one egg (posing a dilemma for conservationists!) which also has a low success rate owing to nest predation (by crows, foxes and free-ranging dogs) and low survival of the chicks.

Rajasthan currently holds an estimated 122 of the c150 remaining Great Indian Bustards in India. The Desert National Park undoubtedly holds the largest population of the bustards[1] in its 3,162 sq.km area.

I was fortunate to see the “GIBs” on the two days that I was at Desert National Park. The first morning, we went on a drive to one of the enclosures near Sudasari. These enclosures are large swathes of fenced-off grasslands that have been made predator and cattle-free to ensure an inviolate space for the bustards to breed and forage. It was still pleasant and the sun wasn’t at its brightest, which was good because I am always wary of sunlight triggering a migraine which can ruin my birding trips! As we reached the enclosure, we drove around and parked our vehicle just outside the metal fence. We stood and waited, eagerly scoping the vast grasslands for the bird. While at it, a huge flock of Greater Short-toed Larks flew by, and a few among them landed in front of us—Black-crowned Sparrow Larks! Behind us, a Red-tailed Shrike perched on top of an acacia, while an Asian Desert Warbler flitted among the short bushes. However, before I could engage with them, my friend pointed out the Great Indian Bustards foraging coolly in the grassland. The three of them, blended perfectly, were difficult to find once you lost sight of them. However, we got used to their presence once we sat and observed them for more than an hour! For a bird with such critically low numbers, it was indeed mesmerising.

Great Indian Bustards have reduced drastically owing to massive hunting in Colonial times and post-independence. Their population is further plagued by conversion of grasslands for development activities[2]. Strikes with high-voltage power lines have caused many GIB fatalities, prompting a Wildlife Institute of India study into how this can be mitigated. Free-ranging dogs in their habitats are another serious threat to the bustard population. The drastically low numbers has led to a multi-institution collaboration between the Rajasthan Forest Department and the Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun. This set in motion the setting up of a breeding centre at Sam in the Desert National Park. Along with expertise from the International Fund for Houbara Conservation in Abu Dhabi, a state-of-the-art centre was set up to breed the birds.

Community participation in the conservation of the Great Indian Bustard has also been commendable as it has given people both a sense of identity as well as an additional source of livelihood through tourism.

Whilst there is an unfortunately realistic chance of Great Indian Bustard becoming the next extinct bird species in India, and in our lifetimes, it is still fairly reliably seen in the Desert National Park. Do consider joining us and seeing this amazing bird, and helping a little towards its conservation, maybe on our GIB-focussed short tour, or a longer tour of Rajasthan and Gujarat.

- Dutta, S., Bhardwaj, G.S., Bhardwaj, D.K., Jhala, Y.V. 2014. Status of Great Indian Bustard and Associated Wildlife in Thar. Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun and Rajasthan Forest Department, Jaipur↩︎

- Dutta, S., Rahmani, A.R. & Jhala, Y.V. Running out of time? The Great Indian bustard Ardeotis nigriceps—status, viability, and conservation strategies. Eur J Wildl Res 57, 615–625 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-010-0472-z↩︎